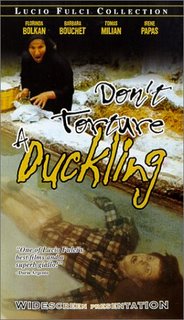

Lucio Fulci's 1972 giallo Don't Torture a Duckling (Non si Sevizia un Paperino) is not his first 'anti-clerical' film - both his comedy The Eroticist (1972) and the historical drama (his favourite among his movies) Beatrice Cenci (1969) contain villainous priests. However the principal subject of Don't Torture a Duckling - the twisted relationship between a priest and his boys - is a particularly difficult and unpleasant one, and caused a certain amount of controversy in Italy upon its release. It makes an interesting contrast with Pedro Almodovar's 2004 film La Mala Educacion (Bad Education), if only because Almodovar and Fulci seem to have such contrasting artistic sensibilities. For example it strikes me that one of Almodovar's defining characteristics is his complete lack of moral severity; in the case, for example, of the miracle baby in All About My Mother 'cured' of HIV, it is as if even the material fact of disease has to retreat before the director's compulsive geniality. In Bad Education, the memories of 'abuse' seem to be memories of something far more ambiguous; one watches with alternating pity and amusement the chance wanderings of people 'following their heart'. Sometimes it leads them to molesting boys, sometimes to murder, and the tears his films unfailingly provoke (at least in me) seem to bubble up from the surface and remain there - by the end of the film my tears have dried up completely, tired of appearing for nothing. Almodovar's camera glosses everything it sees, and he seems to be guided more by pattern and colour composition than by angle or framing. Fulci's eye, on the other hand, curdles everything it sees - anything 'beautiful' at any rate. One watches a Fulci film dry-eyed, despite his repeated presentations of violence and trauma. He uses the position of the camera to definine the moral and emotional weight of his scenes; each shot is a judgement, an act of involvement. The agoraphobic wide-angle compositions of white painted houses and unpaved streets in Don't Torture a Duckling are infused with anger and distaste. Fulci either keeps his distance, shooting from a height, or zooms in as if to point his finger, for example, at a black-clad old woman or a high shuttered window.

Don't Torture a Duckling depicts the murders of young boys somewhere in Southern Italy, strangled or struck with a blow to the head, and follows the police investigation (aided by a visiting journalist from the big city). Suspicion falls on the village idiot, the local witch Maciara, and a beautiful drug-addicted Milanese girl before the real perpetrator is discovered. The plot is involved and complex, in the usual giallo style; it exposes a strange network of complicity and corruption. At moments of repressed emotional tension, of which there are many, Fulci often switches to a hand-held camera. As he alternates between empathetic rage and sardonic moral judgement (as in the chain-whipping and killing of the 'witch' Maciara) he switches between fixed and hand-held shots in a way which conveys the conflicted emotions of the viewer - prurience and revulsion - as much as it does the contrasting perspectives of victim and assailant. The murder of Maciara is Don't Torture a Duckling's most 'celebrated' scene and was a great influence on the ear-slicing sequence in Reservoir Dogs, but the critical thing which so many admirers of Fulci miss is that in Fulci's case this is political. One so often comes across films inspired by directors like Fulci which merely accentuate the blood and entrails (necessary and exciting though they may be) while being utterly deaf to the political content of the originals.

I wonder if Almodovar ever saw Don't Torture a Duckling...? Both films are expertly photographed - in the case of Don't Torture a Duckling the greys and whites of stone and earth contrast with the colours of night rain and a beautiful neon-lit interior scene, but with Fulci rich colour is almost always associated with bodily or moral corruption - he is bitterly suspicious of the sensual. They both contain scenes of boys playing football under priestly supervision, but in Fulci's case he chooses to intercut a scene of boys dressed in white on a green field (in heaven?) with that of a priest falling to his death, his face torn by jutting rocks. Desire and its punishment - an unhappy obsession with purity, and its gleefully filmed consequence in the material collision of stone and skin. In an Almodovar film, death or addiction mean nothing as none of it is really anything more than a play; it's as if, with Wallace Stevens, "the final belief is to believe in a fiction, which you know to be a fiction, there being nothing else." Fulci presents the most outrageous fiction, but grounds its presentation in material squalor; by means of genre and fantasy he conveys the desolation of a world where no escape into fiction is possible. His protagonists in The House by the Cemetery and The Beyond find themselves trapped within the confines of an intruding, ever-narrowing fictional world, in the same way that hard material circumstances or the material fact of death confine or entrap people in their real lives. The image of the white-clad boys playing football at the conclusion of Don't Torture a Duckling mocks the priest's idea of heaven and his idea of purity; the character of the priest's retarded younger sister - on whom the discovery of the culprit turns - mocks his conception of divine justice. The priests in Bad Education are clearly homosexual and motivated by desire, whereas Don Alberto in Don't Torture a Duckling is, as far as I understand the film, celibate and heterosexual by inclination: he murders his boys to protect them from the corruption of women. But the key difference between the films is not in the end the incidentals of the motivating psychology of their villains, but that for Almodovar, desire is a life-giving and creative force, however it may mock and expose those who succumb to it, but that for Fulci desire is an absurdity, that corrupts what it touches and is terminated by death. Fulci simply portrays the waste. No poppies grow out of it.

Of course I prefer Fulci to Almodovar, and not merely because I feel attracted to Fulci's sourness. I think it may be because it's Fulci in the end who seems to point a way out. In Fulci movies doors open up and horrors suddenly emerge from them, or doors appear and lead back to where you came from - to sightless oblivion. His films are full of exits and entrances. If I lived in the world of an Almodovar movie, I might never want to leave it. It would be like choosing darkness over sunlight. But by making his art so cold and allowing no successful escape from the world he presents, Fulci makes the viewer conscious of the confines of the real world and of its material limits. Whether the characters in his movies or the viewer outside can overcome them is a question left unanswered, but it is a question his films constantly provoke. Do the violent-minded, corrupt and superstitious townspeople in Don't Torture a Duckling have any way of reforming their society without modernity simply imposing itself upon them and bringing a new cycle of exploitation? Fulci gives no hint that they can and offers no sentimental dreams about this world or the next. Nothing. That is maybe why his films are so provocative and inspiring. One has to wring the politics out of them. It can be found, for example, in his obsession with doors, bridges, fractures, caves and passageways; each contains a body decomposing, or a skeleton.

And that hints at perhaps the most important question Fulci raises. To what extent is a progressive politics, an ethical life really conceivable, set against the individual reality of bodily decay and death, the final material limit?

Leftcenterleft has a discussion of the movie and some screenshots.

3 comments:

tom, this is a superb post and i'm really interested in this contrast between Fulci and Almodovar (though i have a different take on Almodovar)i've never seen this movie and i'm wondering how available it is...i really hope its the first of many on Fulci.. i wonder if some idea of how he fits into or deviates from the giallo tradition or stands in contrast to Argento (who is definately more of a baroque sensualist) or Mario Bava would be fruitful.... give me a couple of weks and i'll respond with a post on La Mala Educacion on the impostume

Thanks Carl. There's very little criticism around which actually takes Fulci seriously, there's so much to say, but I feel myself floundering a bit sometimes. I've never liked Argento, can't see what his films are about, and their surface qualities leave me cold. Bava I quite like. The giallo tradition is so huge, I don't really feel qualified, but... With regard to Almodovar, to be honest I've never seen his earlier films from the 80s, and I know his work much less well than I know Fulci's, but I find him too... forgiving. Because somehow he seems to absolve the characters in his films, they lose their otherness, that radical ability to cut oneself away from understanding by an evil choice. It's strange, a lot of viewers seem to find him such safe company, considering the characters he presents and the situations he describes. I always start off enjoying his films a lot, and then starting to distrust them about half an hour before the end.

I'm just glad you had the time to read the blog - good luck for 25th November!

Almodovar has certainly demonstrated his awareness of Eurocult cinema before: Matador has clips from Blood and Black Lace and Bloody Moon playing.

Post a Comment