Royal Trux song from 1988

Monday, November 27, 2006

Sunday, November 19, 2006

Thine's like the dread mouth of a fired gun

Catherine Breillat's Anatomy of Hell and Koji Wakamatsu's 1969 film Go, Go, Second Time Virgin have angry, confrontational reputations, but as films they are both rather spare and withdrawn.

Their precise framing and stilted philosophical dialogue work to prevent them breaking down before their subject, keep it within manageable confines. They examine their symptoms, as if tracing the line of a scar with their fingertips. Both have a numbness about them that makes them seem damaged, as if working through a trauma, but they calculatedly use this quality as the seduction-bait with which to attract the viewer.

A girl is raped on the roof of an appartment block by a group of students - it is the second time she has been penetrated and she recalls her first loss of virginity, raped by two boys on the seashore. She remains on the roof after the students have finished with her, gazing at the night sky. The following morning she finds she has bled again - hence the title. She dips her finger into the blood and talks to a boy who has been watching her, and who had masturbated during her rape.

In Anatomy of Hell a Man (Rocco Siffredi) is contracted by a Woman (Amira Cesar) to observe her over four nights when she is "unwatchable"; she challenges her viewer to a kind of spiritual journey using sex as a means, to pass through disgust and anger to something beyond it. The woman provokes him and he attempts to overcome her - he daubs her with lipstick, he inserts a rake-handle into her vagina - acts of childish abuse, or an attempt to create a grotesque artwork. The woman overcomes it by staring past it, by retaining her self-containment, until Siffredi understands that he can never finally destroy her and he cries as she sleeps.

Catherine Breillat has said that there is something royal about the Woman, that she is "reine" and "serene". People often get annoyed with this sort of thing, and bad reviews of both films are not hard to find. The woman with the rake in her bottom has a bandage on her wrist, a badge of self-disgust and self-absorption. The former disgust, its first spiritual level, is turned outward in the course of the film, against the men who have inflicted it. She remembers her childhood, and the faces of the boys playing doctor to her patient.

The same oafishness and incomprehension in these faces as in those of the students -

The raped girl talks with the watching boy, who is impotent except when he masturbates. He has a memory of sexual trauma, of being molested by a nightmarish group of men and women, grabbing at his trousers and writhing amongst themselves - the men retaining their ugly glasses in the way that actors always seem to do in porn films - if not glasses, a silly hat perhaps, or a grotesque moustache.

So the boy, who turns out to be a published poet, kills them all and arranges their bodies in a sculptural pattern. And the girl, who is merely repelled by the sight of their corpses, walks forward into the camera and shouts her defiance, her final declaration: Bakayaro! Bakayaro!, loosely but fairly translated in the subtitles of the Image Entertainment edition as Fuck you! Fuck you! - or fools, or oafs, as one could also translate it. At the end of the film the boy and girl commit suicide, throwing themselves from the roof of the tower block. At the conclusion of Anatomy of Hell, while Rocco Siffredi walks alone by the sea or tells lies about her to the boys in the bar, the Woman is cast/casts herself from a cliff into a violent sea - a flash of gothic white and she is gone.

Both Breillat and Wakamatsu are political radicals, and Breillat at least seems to hope that her films can effect change, might lead forward to a world where they are no longer so necessary. But in both films the conclusion is death, either a return to the ocean, or as in Go, Go, Second Time Virgin, a strange geometrical emptiness, the bodies resting on either side of a white line.

Their precise framing and stilted philosophical dialogue work to prevent them breaking down before their subject, keep it within manageable confines. They examine their symptoms, as if tracing the line of a scar with their fingertips. Both have a numbness about them that makes them seem damaged, as if working through a trauma, but they calculatedly use this quality as the seduction-bait with which to attract the viewer.

A girl is raped on the roof of an appartment block by a group of students - it is the second time she has been penetrated and she recalls her first loss of virginity, raped by two boys on the seashore. She remains on the roof after the students have finished with her, gazing at the night sky. The following morning she finds she has bled again - hence the title. She dips her finger into the blood and talks to a boy who has been watching her, and who had masturbated during her rape.

In Anatomy of Hell a Man (Rocco Siffredi) is contracted by a Woman (Amira Cesar) to observe her over four nights when she is "unwatchable"; she challenges her viewer to a kind of spiritual journey using sex as a means, to pass through disgust and anger to something beyond it. The woman provokes him and he attempts to overcome her - he daubs her with lipstick, he inserts a rake-handle into her vagina - acts of childish abuse, or an attempt to create a grotesque artwork. The woman overcomes it by staring past it, by retaining her self-containment, until Siffredi understands that he can never finally destroy her and he cries as she sleeps.

Catherine Breillat has said that there is something royal about the Woman, that she is "reine" and "serene". People often get annoyed with this sort of thing, and bad reviews of both films are not hard to find. The woman with the rake in her bottom has a bandage on her wrist, a badge of self-disgust and self-absorption. The former disgust, its first spiritual level, is turned outward in the course of the film, against the men who have inflicted it. She remembers her childhood, and the faces of the boys playing doctor to her patient.

The same oafishness and incomprehension in these faces as in those of the students -

The raped girl talks with the watching boy, who is impotent except when he masturbates. He has a memory of sexual trauma, of being molested by a nightmarish group of men and women, grabbing at his trousers and writhing amongst themselves - the men retaining their ugly glasses in the way that actors always seem to do in porn films - if not glasses, a silly hat perhaps, or a grotesque moustache.

So the boy, who turns out to be a published poet, kills them all and arranges their bodies in a sculptural pattern. And the girl, who is merely repelled by the sight of their corpses, walks forward into the camera and shouts her defiance, her final declaration: Bakayaro! Bakayaro!, loosely but fairly translated in the subtitles of the Image Entertainment edition as Fuck you! Fuck you! - or fools, or oafs, as one could also translate it. At the end of the film the boy and girl commit suicide, throwing themselves from the roof of the tower block. At the conclusion of Anatomy of Hell, while Rocco Siffredi walks alone by the sea or tells lies about her to the boys in the bar, the Woman is cast/casts herself from a cliff into a violent sea - a flash of gothic white and she is gone.

Both Breillat and Wakamatsu are political radicals, and Breillat at least seems to hope that her films can effect change, might lead forward to a world where they are no longer so necessary. But in both films the conclusion is death, either a return to the ocean, or as in Go, Go, Second Time Virgin, a strange geometrical emptiness, the bodies resting on either side of a white line.

Thursday, November 16, 2006

The disenchanter

"I don't care about the audience"

Lucio Fulci

Even his fans often find Lucio Fulci's films unsatisfactory; there is usually as much to annoy as there is to please. Sometimes the most flattering reviews contain statements of exasperation or impatience; Fulci films are films for which allowances have to be made.

This is of course precisely why they are so valuable. Fulci had lost interest in go-ahead plot by the early seventies. A Lizard in a Woman's Skin (1971) is on the one hand a police procedural. It is also a study of repression and psychosis not so very different in some respects to Repulsion. But while the film contains a number of dream sequences, the most interesting scenes are those in which the madness of authority integrates itself seamlessly into the private madness of the central character. Carol Hammond is a rich young woman accused of a murder which she had seen herself committing in a dream. While recuperating in a private psychiatric clinic, Carol is chased by a young man who has been hiding in the grounds. After running up some stairs she turns into a corridor with a number of anonymous white doors. Opening one, she finds herself in a vivisection laboratory in which four dogs have been suspended from metal frames and their chests cut open to expose their hearts. They whimper and try to move - the effect is very well done, and comes as a shock to the viewer. Much effort has obviously been expended on the scene, and for what? It adds nothing to the plot - Carol faints to the ground and wakes up in her hospital bed to receive an apology from her doctor, the 'reality' of what she had seen being confirmed. The film then moves on. The viewer is left with the memory of something terrible intruding itself, minimally contextualised - suddenly the film has become more serious, but it is still in no sense a 'serious' film. Of course psychiatric authority is mad/Carol is mad/the dogs are Carol, but the scene is boldest for the way it disrupts the background setting of the 'murder mystery' and forces the viewer's attention. Fulci's scenes of violence (his 'trademark') are always gratuitous, never assimilable into the film as a whole. They are, notoriously, what the fans fast-forward to reach, and by their grotesque power they indelibly stain and highlight the boring bits around them.

Fulci's films are a patchwork, they stop and start, violence erupts out of nowhere and vanishes as quickly as it came. His films are exasperating because they refuse to be consoling. Some film makers like to claim that by showing that "violence has consequences", that "when you sock someone on the jaw, they don't just get up again", they will deny the audience their consoling illusions and force them to reflect on their own capacity for sadism. This is itself a most pernicious illusion. Nothing could be more consoling than to believe that each act of violence is followed by a moralising chain of consequences, or more flattering to the audience than to pretend that they need to be told people bleed when they're hurt. Film makers who reason in such a way are either I suspect in futile pursuit of a prophylaxis - an ultimate act of reportage which will permamently exorcise its viewers' capacity for hatred - or merely pornographers with an incidental taste for the stripped-down and raw. Violence in a Fulci film cannot end in false consolation because it is always uncontextualised - it disrupts the viewer's enjoyment, it makes no sense, it is never explained or exorcised. It cannot titillate because it is either too fantastic, too absurd for belief, or because it is so detailed and explicit that it leaves the viewer himself with no sense of private space from which he can gaze secretly and with pleasure - it is too obvious. Film violence starts to lose its dignity when gazed at for too long - the special effects give out, credibility is lost, or the audience start to find it merely tasteless.

By the time Fulci made The House by the Cemetery (1981), he was no longer interested in providing his audience with the consolations of a resolved plot or coherent motivation. Indeed, House is perhaps his most outrageous film in this respect. Ann the baby sitter has been acting suspiciously. The morning after a visiting estate agent was stabbed through the neck and dragged through the kitchen, we see Ann with a rag and bucket mopping up the blood from the floorboards. Lucy Boyle, the film's wife and mother, has now woken up and comes into the kitchen for her coffee. She makes no comment at all about the enormous blood stain, and she and Ann discuss trivia. It is a scene which many people seem to get indignant about - it is insolent. Of course it can be explained - it symbolises Lucy's capacity for self-deception with regard to the problems in her family, it is a satirical representation of somebody who refuses to see what they don't want to accept - in Lucy's case, her husband's affair with Ann, but these are merely plodding attempts at explication. The principal function of this scene is to disable the viewer's capacity for uncomplicated enjoyment.

In Fulci's 1975 western Four of the Apocalypse the scene abruptly and fantastically shifts from a scorched 'western' landscape to a snow-covered mountain village (filmed in Austria) inhabited entirely by men. Into this society comes professional card-sharp Stubby Preston, on the run from the villains with his pregnant girlfriend Bunny. Bunny is the only female in the village, and after giving birth to a boy, she dies, and the village returns to its all-male state. Stubby leaves the boy in the care of the villagers and returns to the desert. He rides alone. The ending seems set to be consolingly bleak. But as Stubby rides into the distance a little dog starts to follow him, yapping endearingly. The viewer is shocked, almost revolted. The hero has set out alone, but accompanied by a little dog! It is the film's last sudden and disrupting reversal of tone. After all the death and misery portrayed in Four of the Apocaplypse, Fulci refuses to sentimentalise or moralise. Since 'refusing to sentimentalise' is itself a form of sentimentality, the only way Fulci can do this is by introducing the figure of the little dog. The emptiness of the earlier deaths emerge retrospectively in all their bleakness. By ruining the film's expected smooth melancholy closure, everything one has had cause to be melancholy about - the victims of guns or disease - are suddenly recalled to mind, just when the logic of genre expectation would have buried them.

Lucio Fulci

Even his fans often find Lucio Fulci's films unsatisfactory; there is usually as much to annoy as there is to please. Sometimes the most flattering reviews contain statements of exasperation or impatience; Fulci films are films for which allowances have to be made.

This is of course precisely why they are so valuable. Fulci had lost interest in go-ahead plot by the early seventies. A Lizard in a Woman's Skin (1971) is on the one hand a police procedural. It is also a study of repression and psychosis not so very different in some respects to Repulsion. But while the film contains a number of dream sequences, the most interesting scenes are those in which the madness of authority integrates itself seamlessly into the private madness of the central character. Carol Hammond is a rich young woman accused of a murder which she had seen herself committing in a dream. While recuperating in a private psychiatric clinic, Carol is chased by a young man who has been hiding in the grounds. After running up some stairs she turns into a corridor with a number of anonymous white doors. Opening one, she finds herself in a vivisection laboratory in which four dogs have been suspended from metal frames and their chests cut open to expose their hearts. They whimper and try to move - the effect is very well done, and comes as a shock to the viewer. Much effort has obviously been expended on the scene, and for what? It adds nothing to the plot - Carol faints to the ground and wakes up in her hospital bed to receive an apology from her doctor, the 'reality' of what she had seen being confirmed. The film then moves on. The viewer is left with the memory of something terrible intruding itself, minimally contextualised - suddenly the film has become more serious, but it is still in no sense a 'serious' film. Of course psychiatric authority is mad/Carol is mad/the dogs are Carol, but the scene is boldest for the way it disrupts the background setting of the 'murder mystery' and forces the viewer's attention. Fulci's scenes of violence (his 'trademark') are always gratuitous, never assimilable into the film as a whole. They are, notoriously, what the fans fast-forward to reach, and by their grotesque power they indelibly stain and highlight the boring bits around them.

Fulci's films are a patchwork, they stop and start, violence erupts out of nowhere and vanishes as quickly as it came. His films are exasperating because they refuse to be consoling. Some film makers like to claim that by showing that "violence has consequences", that "when you sock someone on the jaw, they don't just get up again", they will deny the audience their consoling illusions and force them to reflect on their own capacity for sadism. This is itself a most pernicious illusion. Nothing could be more consoling than to believe that each act of violence is followed by a moralising chain of consequences, or more flattering to the audience than to pretend that they need to be told people bleed when they're hurt. Film makers who reason in such a way are either I suspect in futile pursuit of a prophylaxis - an ultimate act of reportage which will permamently exorcise its viewers' capacity for hatred - or merely pornographers with an incidental taste for the stripped-down and raw. Violence in a Fulci film cannot end in false consolation because it is always uncontextualised - it disrupts the viewer's enjoyment, it makes no sense, it is never explained or exorcised. It cannot titillate because it is either too fantastic, too absurd for belief, or because it is so detailed and explicit that it leaves the viewer himself with no sense of private space from which he can gaze secretly and with pleasure - it is too obvious. Film violence starts to lose its dignity when gazed at for too long - the special effects give out, credibility is lost, or the audience start to find it merely tasteless.

By the time Fulci made The House by the Cemetery (1981), he was no longer interested in providing his audience with the consolations of a resolved plot or coherent motivation. Indeed, House is perhaps his most outrageous film in this respect. Ann the baby sitter has been acting suspiciously. The morning after a visiting estate agent was stabbed through the neck and dragged through the kitchen, we see Ann with a rag and bucket mopping up the blood from the floorboards. Lucy Boyle, the film's wife and mother, has now woken up and comes into the kitchen for her coffee. She makes no comment at all about the enormous blood stain, and she and Ann discuss trivia. It is a scene which many people seem to get indignant about - it is insolent. Of course it can be explained - it symbolises Lucy's capacity for self-deception with regard to the problems in her family, it is a satirical representation of somebody who refuses to see what they don't want to accept - in Lucy's case, her husband's affair with Ann, but these are merely plodding attempts at explication. The principal function of this scene is to disable the viewer's capacity for uncomplicated enjoyment.

In Fulci's 1975 western Four of the Apocalypse the scene abruptly and fantastically shifts from a scorched 'western' landscape to a snow-covered mountain village (filmed in Austria) inhabited entirely by men. Into this society comes professional card-sharp Stubby Preston, on the run from the villains with his pregnant girlfriend Bunny. Bunny is the only female in the village, and after giving birth to a boy, she dies, and the village returns to its all-male state. Stubby leaves the boy in the care of the villagers and returns to the desert. He rides alone. The ending seems set to be consolingly bleak. But as Stubby rides into the distance a little dog starts to follow him, yapping endearingly. The viewer is shocked, almost revolted. The hero has set out alone, but accompanied by a little dog! It is the film's last sudden and disrupting reversal of tone. After all the death and misery portrayed in Four of the Apocaplypse, Fulci refuses to sentimentalise or moralise. Since 'refusing to sentimentalise' is itself a form of sentimentality, the only way Fulci can do this is by introducing the figure of the little dog. The emptiness of the earlier deaths emerge retrospectively in all their bleakness. By ruining the film's expected smooth melancholy closure, everything one has had cause to be melancholy about - the victims of guns or disease - are suddenly recalled to mind, just when the logic of genre expectation would have buried them.

Wednesday, November 08, 2006

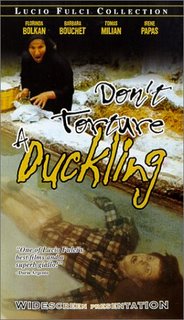

Don't Torture Donald Duck

Lucio Fulci's 1972 giallo Don't Torture a Duckling (Non si Sevizia un Paperino) is not his first 'anti-clerical' film - both his comedy The Eroticist (1972) and the historical drama (his favourite among his movies) Beatrice Cenci (1969) contain villainous priests. However the principal subject of Don't Torture a Duckling - the twisted relationship between a priest and his boys - is a particularly difficult and unpleasant one, and caused a certain amount of controversy in Italy upon its release. It makes an interesting contrast with Pedro Almodovar's 2004 film La Mala Educacion (Bad Education), if only because Almodovar and Fulci seem to have such contrasting artistic sensibilities. For example it strikes me that one of Almodovar's defining characteristics is his complete lack of moral severity; in the case, for example, of the miracle baby in All About My Mother 'cured' of HIV, it is as if even the material fact of disease has to retreat before the director's compulsive geniality. In Bad Education, the memories of 'abuse' seem to be memories of something far more ambiguous; one watches with alternating pity and amusement the chance wanderings of people 'following their heart'. Sometimes it leads them to molesting boys, sometimes to murder, and the tears his films unfailingly provoke (at least in me) seem to bubble up from the surface and remain there - by the end of the film my tears have dried up completely, tired of appearing for nothing. Almodovar's camera glosses everything it sees, and he seems to be guided more by pattern and colour composition than by angle or framing. Fulci's eye, on the other hand, curdles everything it sees - anything 'beautiful' at any rate. One watches a Fulci film dry-eyed, despite his repeated presentations of violence and trauma. He uses the position of the camera to definine the moral and emotional weight of his scenes; each shot is a judgement, an act of involvement. The agoraphobic wide-angle compositions of white painted houses and unpaved streets in Don't Torture a Duckling are infused with anger and distaste. Fulci either keeps his distance, shooting from a height, or zooms in as if to point his finger, for example, at a black-clad old woman or a high shuttered window.

Don't Torture a Duckling depicts the murders of young boys somewhere in Southern Italy, strangled or struck with a blow to the head, and follows the police investigation (aided by a visiting journalist from the big city). Suspicion falls on the village idiot, the local witch Maciara, and a beautiful drug-addicted Milanese girl before the real perpetrator is discovered. The plot is involved and complex, in the usual giallo style; it exposes a strange network of complicity and corruption. At moments of repressed emotional tension, of which there are many, Fulci often switches to a hand-held camera. As he alternates between empathetic rage and sardonic moral judgement (as in the chain-whipping and killing of the 'witch' Maciara) he switches between fixed and hand-held shots in a way which conveys the conflicted emotions of the viewer - prurience and revulsion - as much as it does the contrasting perspectives of victim and assailant. The murder of Maciara is Don't Torture a Duckling's most 'celebrated' scene and was a great influence on the ear-slicing sequence in Reservoir Dogs, but the critical thing which so many admirers of Fulci miss is that in Fulci's case this is political. One so often comes across films inspired by directors like Fulci which merely accentuate the blood and entrails (necessary and exciting though they may be) while being utterly deaf to the political content of the originals.

I wonder if Almodovar ever saw Don't Torture a Duckling...? Both films are expertly photographed - in the case of Don't Torture a Duckling the greys and whites of stone and earth contrast with the colours of night rain and a beautiful neon-lit interior scene, but with Fulci rich colour is almost always associated with bodily or moral corruption - he is bitterly suspicious of the sensual. They both contain scenes of boys playing football under priestly supervision, but in Fulci's case he chooses to intercut a scene of boys dressed in white on a green field (in heaven?) with that of a priest falling to his death, his face torn by jutting rocks. Desire and its punishment - an unhappy obsession with purity, and its gleefully filmed consequence in the material collision of stone and skin. In an Almodovar film, death or addiction mean nothing as none of it is really anything more than a play; it's as if, with Wallace Stevens, "the final belief is to believe in a fiction, which you know to be a fiction, there being nothing else." Fulci presents the most outrageous fiction, but grounds its presentation in material squalor; by means of genre and fantasy he conveys the desolation of a world where no escape into fiction is possible. His protagonists in The House by the Cemetery and The Beyond find themselves trapped within the confines of an intruding, ever-narrowing fictional world, in the same way that hard material circumstances or the material fact of death confine or entrap people in their real lives. The image of the white-clad boys playing football at the conclusion of Don't Torture a Duckling mocks the priest's idea of heaven and his idea of purity; the character of the priest's retarded younger sister - on whom the discovery of the culprit turns - mocks his conception of divine justice. The priests in Bad Education are clearly homosexual and motivated by desire, whereas Don Alberto in Don't Torture a Duckling is, as far as I understand the film, celibate and heterosexual by inclination: he murders his boys to protect them from the corruption of women. But the key difference between the films is not in the end the incidentals of the motivating psychology of their villains, but that for Almodovar, desire is a life-giving and creative force, however it may mock and expose those who succumb to it, but that for Fulci desire is an absurdity, that corrupts what it touches and is terminated by death. Fulci simply portrays the waste. No poppies grow out of it.

Of course I prefer Fulci to Almodovar, and not merely because I feel attracted to Fulci's sourness. I think it may be because it's Fulci in the end who seems to point a way out. In Fulci movies doors open up and horrors suddenly emerge from them, or doors appear and lead back to where you came from - to sightless oblivion. His films are full of exits and entrances. If I lived in the world of an Almodovar movie, I might never want to leave it. It would be like choosing darkness over sunlight. But by making his art so cold and allowing no successful escape from the world he presents, Fulci makes the viewer conscious of the confines of the real world and of its material limits. Whether the characters in his movies or the viewer outside can overcome them is a question left unanswered, but it is a question his films constantly provoke. Do the violent-minded, corrupt and superstitious townspeople in Don't Torture a Duckling have any way of reforming their society without modernity simply imposing itself upon them and bringing a new cycle of exploitation? Fulci gives no hint that they can and offers no sentimental dreams about this world or the next. Nothing. That is maybe why his films are so provocative and inspiring. One has to wring the politics out of them. It can be found, for example, in his obsession with doors, bridges, fractures, caves and passageways; each contains a body decomposing, or a skeleton.

And that hints at perhaps the most important question Fulci raises. To what extent is a progressive politics, an ethical life really conceivable, set against the individual reality of bodily decay and death, the final material limit?

Leftcenterleft has a discussion of the movie and some screenshots.

Saturday, November 04, 2006

Easy mistakes to make

A time for angry tears and regrets. In a speech to Khmer Rouge cadres on the Thai-Cambodian border, Pol Pot compared his Democratic Kampuchean government to a baby taking its first steps and not unnaturally acting clumsily and ending up breaking things. One always imagines, for example, that 6o0,000 people would be quite hard to kill. But let loose a giant baby, and things can deteriorate surprisingly quickly. 750,000 people are estimated to have been killed by the American B52 raids inside Cambodia in pursuit of Viet Cong infiltrators, a slaughter which was of course decisive in strengthening the Khmer Rouge. 750,000 is a conservative estimate of the numbers killed as a matter of policy (rather than 'inadvertently' through famine) during Pol Pot's time in power.

Vanity Fair collects second thoughts from Richard Perle and other like-minded fainthearts while Giorgio Fabretti appeals on behalf of the Save Pol Pot Fund

Pol Pot spoke as the representative of the military. He says that he knows that many people in the country hate him and think he's responsible for the killings. He said that he knows many people died. When he said this he nearly broke down and cried. He said he must accept responsibility because the line was too far to the left, and because he didn't keep proper track of what was going on. He said he was like the master in a house who didn't know what the kids were up to, and that he trusted people too much. For example, he allowed Chhim Samauk to take care of central committee business for him, and Sao Phim to take care of political education... These were people to whom he felt very close, and he trusted them completely. Then in the end... they made a mess of everything. ...They would tell him things that were not true, that everything was fine, but that this person or that was a traitor. In the end they were the real traitors.

from Brother Number One by David Chandler, pg. 171

Vanity Fair collects second thoughts from Richard Perle and other like-minded fainthearts while Giorgio Fabretti appeals on behalf of the Save Pol Pot Fund

Pol Pot spoke as the representative of the military. He says that he knows that many people in the country hate him and think he's responsible for the killings. He said that he knows many people died. When he said this he nearly broke down and cried. He said he must accept responsibility because the line was too far to the left, and because he didn't keep proper track of what was going on. He said he was like the master in a house who didn't know what the kids were up to, and that he trusted people too much. For example, he allowed Chhim Samauk to take care of central committee business for him, and Sao Phim to take care of political education... These were people to whom he felt very close, and he trusted them completely. Then in the end... they made a mess of everything. ...They would tell him things that were not true, that everything was fine, but that this person or that was a traitor. In the end they were the real traitors.

from Brother Number One by David Chandler, pg. 171

Thursday, November 02, 2006

from His Toy, His Dream, His Rest

My eyes with which I see so easily

will become closed. My friendly heart will stop.

I won't sit up.

Nose me, soon you won't like it - ee -

worse than a pesthouse; and my thought all gone

& the vanish of the sun.

The vanish of the moon, which Henry loved

on charming nights when Henry young was moved

by delicate ladies

with ripped-off panties, mouths open to kiss.

They say the coffin closes without a sound

& is lowered underground!

So now his thought's gone, buried his body dead,

what now about the adorable Little Twiss

& his fair lady,

will they set up a tumult in his praise

will assistant professors become associates

by working on his works?

John Berryman, Dream Song 373

will become closed. My friendly heart will stop.

I won't sit up.

Nose me, soon you won't like it - ee -

worse than a pesthouse; and my thought all gone

& the vanish of the sun.

The vanish of the moon, which Henry loved

on charming nights when Henry young was moved

by delicate ladies

with ripped-off panties, mouths open to kiss.

They say the coffin closes without a sound

& is lowered underground!

So now his thought's gone, buried his body dead,

what now about the adorable Little Twiss

& his fair lady,

will they set up a tumult in his praise

will assistant professors become associates

by working on his works?

John Berryman, Dream Song 373

Wednesday, November 01, 2006

Lucio Fulci

1.

Andrei Tarkovsky, while he worked in Italy on Nostalgia, attended a screening of Lucio Fulci's first and most celebrated horror film Zombie Flesheaters, and described it in his diary as "ghastly, repulsive trash".

One thing that I like about films is that there really are no respectable ones, none that are quite gentlemen - not even Tarkovsky, although he comes perilously close. There isn't a clear canon, no films that one simply has to have seen to account oneself educated, and I think we just about find it possible to love anything, reject anything, and not stoop to forcing an interest. And film critics are so fallible - people like David Thomson write with as little (or as arbitrarily minute) an attention to detail and as much offhand authority as someone like Pliny the Elder, and it makes them both irritating and unintimidating - it keeps the field open. I like the wretched disservice it does to directors like Lucio Fulci, director of A Lizard in a Woman's Skin, Don't Torture a Duckling, City of the Living Dead, The New York Ripper - unannotated, unassimilated, uncontained within any respectable bounds.

Fulci himself had a complex and divided attitude to his own work. On the one hand he knew he was a hack, working in a variety of popular genres: comedies, thrillers, westerns, horror - whatever made money. On the other, he saw himself as the student of Visconti, the heir of Bunuel, a man attracted to the structures of genre but compelled by a mixture of wilfulness and artistic seriousness to sabotage them. He is well known in this respect for directing two thirds of a film "with his left hand", as the Italians say, and then suddenly spoiling the fun with something jarring, something felt, something truthfully disquieting. I like his work very much, although I started out by despising it. The moment came after sitting through The House by the Cemetery one rainy afternoon and suddenly wondering, what if this apparent incompetence is actually artfulness, what if - just suppose - Fulci knows what he's doing?

I find the shock of the new first communicates itself to me as ineptitude, and the contempt I feel causes me to replay the thing over and over again in my mind as an exhibit for derision until I become half-guiltily conscious of my fascination. The choice is either to reject it with a sort of Stalinist moral sternness, or to submit to it like an infection and see what it makes of me.

Fulci is famous (among horror fans) for what, exactly?

For an obsession with eyeballs and their mutilation, for longueurs punctuated by scenes of grotesque violence, for derivative, badly acted, structureless films which for some reason find themselves banned under the provisions of the Video Recordings Act and accrue themselves an undeserved cult reputation. Only.... Fulci suddenly reminded me now of John Berryman and the Dream Songs, language hacked into pieces, loudmouthed and half-ful of it, grandiose and threadbare, threatening suicide. And I want in the next few posts to focus on a few of Lucio Fulci's films, my favourites, and elucidate some of their virtues (to speak tiptoeingly like I'm critiquing Berryman or someone).

Andrei Tarkovsky, while he worked in Italy on Nostalgia, attended a screening of Lucio Fulci's first and most celebrated horror film Zombie Flesheaters, and described it in his diary as "ghastly, repulsive trash".

One thing that I like about films is that there really are no respectable ones, none that are quite gentlemen - not even Tarkovsky, although he comes perilously close. There isn't a clear canon, no films that one simply has to have seen to account oneself educated, and I think we just about find it possible to love anything, reject anything, and not stoop to forcing an interest. And film critics are so fallible - people like David Thomson write with as little (or as arbitrarily minute) an attention to detail and as much offhand authority as someone like Pliny the Elder, and it makes them both irritating and unintimidating - it keeps the field open. I like the wretched disservice it does to directors like Lucio Fulci, director of A Lizard in a Woman's Skin, Don't Torture a Duckling, City of the Living Dead, The New York Ripper - unannotated, unassimilated, uncontained within any respectable bounds.

Fulci himself had a complex and divided attitude to his own work. On the one hand he knew he was a hack, working in a variety of popular genres: comedies, thrillers, westerns, horror - whatever made money. On the other, he saw himself as the student of Visconti, the heir of Bunuel, a man attracted to the structures of genre but compelled by a mixture of wilfulness and artistic seriousness to sabotage them. He is well known in this respect for directing two thirds of a film "with his left hand", as the Italians say, and then suddenly spoiling the fun with something jarring, something felt, something truthfully disquieting. I like his work very much, although I started out by despising it. The moment came after sitting through The House by the Cemetery one rainy afternoon and suddenly wondering, what if this apparent incompetence is actually artfulness, what if - just suppose - Fulci knows what he's doing?

I find the shock of the new first communicates itself to me as ineptitude, and the contempt I feel causes me to replay the thing over and over again in my mind as an exhibit for derision until I become half-guiltily conscious of my fascination. The choice is either to reject it with a sort of Stalinist moral sternness, or to submit to it like an infection and see what it makes of me.

Fulci is famous (among horror fans) for what, exactly?

For an obsession with eyeballs and their mutilation, for longueurs punctuated by scenes of grotesque violence, for derivative, badly acted, structureless films which for some reason find themselves banned under the provisions of the Video Recordings Act and accrue themselves an undeserved cult reputation. Only.... Fulci suddenly reminded me now of John Berryman and the Dream Songs, language hacked into pieces, loudmouthed and half-ful of it, grandiose and threadbare, threatening suicide. And I want in the next few posts to focus on a few of Lucio Fulci's films, my favourites, and elucidate some of their virtues (to speak tiptoeingly like I'm critiquing Berryman or someone).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)