Wednesday, November 23, 2005

Tuesday, November 22, 2005

I was once invited outside for a fight by a fan of the Dead Kennedys for suggesting that the song Police Truck might be interpreted as pro-police. It documents a scene of police brutality accompanied by a pruriently righteous guitar part. It's an early song, and the Kennedys themselves evolved a more politically constructive lyrical and musical style. From the leering aggression of Saturday Night Holocaust to the fair-minded suggestions of Stars and Stripes of Corruption ("How about more art and theatre instead of sports?") the Dead Kennedys certainly made a rational political journey. But the music was somehow neutered, and everyone prefers the early work, rage and moral nihilism notwithstanding. The Kennedys ran up against the limitations of punk, of a restricted aesthetic. Unprepared to burst their musical boundaries, they gave up the ghost and disbanded. They had no tools to advance their style without diluting it. Kurt Cobain's suicide I interpret as a musical admission of defeat, among other things. There was nowhere else for Nirvana to go without abandoning the Seattle sound entirely. Despite his political engagement, he ended up trapped in his aesthetic graveyard; improvising freely at the end of a performance, "did you really pay to listen to this shit?" he asked the audience. But by decisively abndoning his fans and truly investigating the "shit" they resented, he might have saved his art.

Perhaps there is no rational political future. Perhaps there is only continued existence and grey variations of more of the same. The films of Lucio Fulci convey this philosophy with open-eyed horror. The drab grey hell of The Beyond is a symbolic representation of the non-possibility of any fundamental change in economic or social relations. Beyond this world, suggests Fulci, is a pale waste inhabited by homeless alcoholics. We are condemned, in this world and the next, merely to feed and to wander. His hero and heroine, abruptly transfered to the afterlife, find they have become blind. There will be no redemption or change. Fulci himself, as a Catholic and an anti-fascist, shrank from the horror of this, but despite himself he was unable to film happy endings.

If religion provides only illusory comfort, and if Marxism too is an illusion, if there is no religious or secular hope, one ends, in Art, with the repetitive and destructive emptiness depicted by Fulci, or the weary estrangement of this poem by Kipling, one of his Epitaphs of the War:

SALONIKAN GRAVE

I have watched a thousand days

Push out and crawl into night

Slowly as tortoises.

Now I, too, follow these.

It is fever, and not the fight -

Time, not battle - that slays.

Rudyard Kipling

Perhaps there is no rational political future. Perhaps there is only continued existence and grey variations of more of the same. The films of Lucio Fulci convey this philosophy with open-eyed horror. The drab grey hell of The Beyond is a symbolic representation of the non-possibility of any fundamental change in economic or social relations. Beyond this world, suggests Fulci, is a pale waste inhabited by homeless alcoholics. We are condemned, in this world and the next, merely to feed and to wander. His hero and heroine, abruptly transfered to the afterlife, find they have become blind. There will be no redemption or change. Fulci himself, as a Catholic and an anti-fascist, shrank from the horror of this, but despite himself he was unable to film happy endings.

If religion provides only illusory comfort, and if Marxism too is an illusion, if there is no religious or secular hope, one ends, in Art, with the repetitive and destructive emptiness depicted by Fulci, or the weary estrangement of this poem by Kipling, one of his Epitaphs of the War:

SALONIKAN GRAVE

I have watched a thousand days

Push out and crawl into night

Slowly as tortoises.

Now I, too, follow these.

It is fever, and not the fight -

Time, not battle - that slays.

Rudyard Kipling

Kim Longinotto, the truth, and the human

I've just come back from a screening of the documentary Sisters in Law, by Kim Longinotto, who also directed Divorce Iranian Style. Both are filmed without commentary, and follow the stories of various women trying to seek justice for themselves within a traditional legal system. Sisters in Law was filmed in Cameroon with Florence Ayisi, and follows a number of cases - for example that of a Muslim woman called Amina, who succesfully prosecutes and divorces her husband for beating and abusing her. She was the first woman to obtain such a prosecution in her area, and she was helped by a group of Cameroonian women lawyers, prosecutors and activists. It would be fatuous to call the film inspiring, since the stories were so sad and the lives they described were so harsh, and, besides, the fight belongs to them and not to well-meaning observers. But the film concluded with the first Cameroonian woman judge introducing Amina to her legal students - most of them women - and showing to them by inspiring example, how a brave stand by a single individual could force society to change.

Kim Longinotto was present at the screening to answer questions at the end. One criticism raised was that as a Western woman filming the proceedings, she was inevitably going to be intervening herself in the world that she films, and that she couldn't pretend to be some kind of 'neutral observer'. Longinotto readily conceded this, and made quite clear that she was engaged, as a film maker, in the struggles she documented. Amina was apparently very keen for her case to be filmed, and this was clearly, in part, in order to exert pressure on the judges, who would be conscious that their decision would be made "in the eyes of the world". On the other hand, it is strange, remarked Kim Longinotto, how soon people forget that the camera is present, and Amina, on returning home from court, was asked "Were there any other women there with you?", and she replied, quite unselfconsciously, "No! Only me!" It's interesting in that respect that Longinotto uses quite a large camera, and avoids using hidden cameras, and this may paradoxically result in more natural behaviour.

The film was made without commentary, and Longinotto was also criticised for this, for not contextualising the society which she filmed... "What is the ratio of Muslims to Christians in Cameroon?" "What are the various language and ethnic divisions?" But, in truth, no amount of contextual facts will force the viewer to perceive another society with a humane sensibility. Longinotto changes the world through her films by first altering bare perceptions, by appealing to conscience. And it is only on such a base that facts have much relevance or use. I saw Divorce Iranian Style in 1998 and it was the first time I had ever seen Iranians outside the Death to America pantomimes or war reporting. And any slight knowledge I have of Iran, based on books like Roy Mottahadeh's The Mantle of the Prophet, was founded on the first shock of human recognition. Talk of airstrikes on Iran with nuclear-tipped warheads is absolutely dependent on people never seeing films like Divorce Iranian Style, or Longinotto's other Iranian documentary Runaway. One of the most popular Iranian films in recent years was a satire on the clergy, called The Lizard. It has great popular appeal, but it was only ever shown in the UK at the ICA as far as I'm aware and is only commercially available on a wretched bootleg from iranian.com. When Iranian graphic artist Marjane Satrapi visited Utah to give a reading, someone asked her "Can you see the moon from Iran?" Artists like Longinotto and Satrapi have to build on a surface of almost complete ignorance, but the question is actually a rather sweetly poetic one - and the questioner at least had the interest to attend a talk by Satrapi. When al-Jazeera interviewed Israeli politicians, I believe it was the first time many in the region had heard an Israeli speak. There are actually very few Israeli films released in the West; while its news profile is very high, its cultural - its human - profile is almost non-existent. And if that is true in the West, it is probably all the more true in the Arab world. It helps aid the process of demonization. "Where are your horns?", my Israeli colleague was asked.

Longinotto prefers to film in medium shots, avoiding close-ups, rapid cutting or ostentatious camera-work. It is a very modest, unobtrusive style. That may in part be the reason for the immense emotional power of her work. Her films almost always bring tears to the eyes, tears of longing and of shame on the part of the viewer, not so much the smug tears of empathy. It is the longing to make a connection, to reach out an authentic hand. And the means by which Longinotto consistently achieves this is mysterious. To me, it is an alchemy produced by her engagement, by the value her art places on justice and truth. The greatest art is a moral challenge to the viewer and is itself the product of a moral sensibility. The alternative is amusing, but does no more than fiddle at the burning. I was reminded, watching Sisters in Law and listening to Longinotto, of Peter Watkins, of Culloden and Punishment Park ....and also of Paul Morrissey and Andy Warhol.

Morrissey is quoted in Bob Colacello's memoir and biography of Warhol, Holy Terror, as saying to him, "I mean, what could be more ridiculous than the pompous, pseudointellectual notion that the director is the most important person on a movie? Everyone knows the most important person on a movie is the star!" Morrissey, Longinotto and Watkins are united by their determination to efface themselves as artists before what they film, for their moral commitment, unsparing and hostile to compromise, and by the mysterious power of their work, bestowed like a blessing upon the righteous, and impossible to fake or imitate. Aleister Crowley wrote in Liber AL vel Legis, "Every man and every woman is a star", and between the starry potential envisaged by Crowley and the grimy, abject starriness of a Morrissey subject, are the figures of Amina in Sisters in Law, or the little girl taking the place of her clerical father in Divorce Iranian Style, and dispensing satirical justice from his chair. They are stars, and Longinotto their committed observer.

The BrightLights Film Journal has an overview of Longinotto's work here

And Red Pepper has a very brief interview

Thursday, November 17, 2005

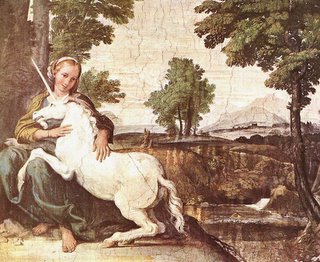

So wary as to disappear for centuries and reappear,

yet never to be caught,

the unicorn has been preserved

by an unmatched device

wrought like the work of expert blacksmiths -

this animal of that one horn

throwing itself upon which headforemost from a cliff,

it walks away unharmed;

proficient in this feat which, like Herodotus,

I have not seen except in pictures.

Thus this strange animal with its miraculous elusiveness,

has come to be unique,

"impossible to take alive,"

tamed only by a lady inoffensive like itself -

as curiously wild and gentle;

"as straight and slender as the crest,

or antlet of the one-beam'd beast."

Upon the printed page,

also by word of mouth,

we have a record of it all

and how, unfearful of deceit,

etched like an equine monster of an old celestial map,

beside a cloud or dress of Virgin-Mary blue,

improved "all over slightly with shakes of Venice gold,

and silver, and some O's,"

the unicorn "with pavon high," approaches eagerly;

until engrossed by what appears of this strange enemy,

upon the map, "upon her lap,"

its "mild wild head doth lie."

from Sea Unicorns and Land Unicorns by Marianne Moore

yet never to be caught,

the unicorn has been preserved

by an unmatched device

wrought like the work of expert blacksmiths -

this animal of that one horn

throwing itself upon which headforemost from a cliff,

it walks away unharmed;

proficient in this feat which, like Herodotus,

I have not seen except in pictures.

Thus this strange animal with its miraculous elusiveness,

has come to be unique,

"impossible to take alive,"

tamed only by a lady inoffensive like itself -

as curiously wild and gentle;

"as straight and slender as the crest,

or antlet of the one-beam'd beast."

Upon the printed page,

also by word of mouth,

we have a record of it all

and how, unfearful of deceit,

etched like an equine monster of an old celestial map,

beside a cloud or dress of Virgin-Mary blue,

improved "all over slightly with shakes of Venice gold,

and silver, and some O's,"

the unicorn "with pavon high," approaches eagerly;

until engrossed by what appears of this strange enemy,

upon the map, "upon her lap,"

its "mild wild head doth lie."

from Sea Unicorns and Land Unicorns by Marianne Moore

Wednesday, November 16, 2005

Sleeptree songs

Four poems from Heian Japan

from Lady Ki to Otomo no Yakamochi, with a sleeptree flower and some reed blossoms...

For you, my slave,

I picked these reed blossoms

From the fields of spring

With my own hands.

Eat them and grow fat.

Should the mistress alone

See the sleeptree,

That opens in the day

And sleeps in love at night?

Look upon it too, slave.

He replies:

This slave must be longing

For his mistress -

Though I eat the buds of reed you send,

I grow but thinner, thinner.

The sleeptree you sent, love,

That I might think of you,

Will only bear flowers,

Never bear fruit.

Lady Ki was older than Yakamochi and the wife of an imperial prince, while Yakamochi (718 - 785) was a lower ranking courtier. The sleeptree is the mimosa, which folds up its leaves and "sleeps" at night. Its name, nebu or nemu, sounds like the word for sleep, and the characters with which it is written have erotic connotations, "untie pleasure".

from A Warbler's Song in the Dusk - The Life & Work of Otomo Yakamochi by Paula Doe

from Lady Ki to Otomo no Yakamochi, with a sleeptree flower and some reed blossoms...

For you, my slave,

I picked these reed blossoms

From the fields of spring

With my own hands.

Eat them and grow fat.

Should the mistress alone

See the sleeptree,

That opens in the day

And sleeps in love at night?

Look upon it too, slave.

He replies:

This slave must be longing

For his mistress -

Though I eat the buds of reed you send,

I grow but thinner, thinner.

The sleeptree you sent, love,

That I might think of you,

Will only bear flowers,

Never bear fruit.

Lady Ki was older than Yakamochi and the wife of an imperial prince, while Yakamochi (718 - 785) was a lower ranking courtier. The sleeptree is the mimosa, which folds up its leaves and "sleeps" at night. Its name, nebu or nemu, sounds like the word for sleep, and the characters with which it is written have erotic connotations, "untie pleasure".

from A Warbler's Song in the Dusk - The Life & Work of Otomo Yakamochi by Paula Doe

Tuesday, November 15, 2005

Elm

for Ruth Fainlight

I know the bottom, she says. I know it with my great tap root;

It is what you fear.

I do not fear it: I have been there.

Is it the sea you hear in me,

Its dissatisfactions?

Or the voice of nothing, that was your madness?

Love is a shadow.

How you lie and cry after it.

Listen: these are its hooves: it has gone off, like a horse.

All night I shall gallop thus, impetuously,

Till your head is a stone, your pillow a little turf,

Echoing, echoing.

Or shall I bring you the sound of poisons?

This is rain now, the big hush.

And this is the fruit of it: tin white, like arsenic.

I have suffered the atrocity of sunsets.

Scorched to the root

My red filaments burn and stand, a hand of wires.

Now I break up in pieces that fly about like clubs.

A wind of such violence

Will tolerate no bystanding: I must shriek.

The moon, also, is merciless: she would drag me

Cruelly, being barren.

Her radience scathes me. Or perhaps I have caught her.

I let her go. I let her go

Diminshed and flat, as after radical surgery.

How your bad dreams possess and endow me.

I am inhabited by a cry.

Nightly it flaps out

Looking, with its hooks, for something to love.

I am terrified by this dark thing

That sleeps in me;

All day I feel its soft, feathery turnings, its malignity.

Clouds pass and disperse.

Are those the faces of love, those pale irretrievables?

Is it for such I agitate my heart?

I am incapable of more knowledge.

What is this, this face

So murderous in its strangle of branches?--

Its snaky acids kiss.

It petrifies the will. These are the isolate, slow faults

That kill, that kill, that kill.

Sylvia Plath

I know the bottom, she says. I know it with my great tap root;

It is what you fear.

I do not fear it: I have been there.

Is it the sea you hear in me,

Its dissatisfactions?

Or the voice of nothing, that was your madness?

Love is a shadow.

How you lie and cry after it.

Listen: these are its hooves: it has gone off, like a horse.

All night I shall gallop thus, impetuously,

Till your head is a stone, your pillow a little turf,

Echoing, echoing.

Or shall I bring you the sound of poisons?

This is rain now, the big hush.

And this is the fruit of it: tin white, like arsenic.

I have suffered the atrocity of sunsets.

Scorched to the root

My red filaments burn and stand, a hand of wires.

Now I break up in pieces that fly about like clubs.

A wind of such violence

Will tolerate no bystanding: I must shriek.

The moon, also, is merciless: she would drag me

Cruelly, being barren.

Her radience scathes me. Or perhaps I have caught her.

I let her go. I let her go

Diminshed and flat, as after radical surgery.

How your bad dreams possess and endow me.

I am inhabited by a cry.

Nightly it flaps out

Looking, with its hooks, for something to love.

I am terrified by this dark thing

That sleeps in me;

All day I feel its soft, feathery turnings, its malignity.

Clouds pass and disperse.

Are those the faces of love, those pale irretrievables?

Is it for such I agitate my heart?

I am incapable of more knowledge.

What is this, this face

So murderous in its strangle of branches?--

Its snaky acids kiss.

It petrifies the will. These are the isolate, slow faults

That kill, that kill, that kill.

Sylvia Plath

Monday, November 14, 2005

CGI is the death of theatre, yawn.

There is a scene in Cannibal Holocaust where the Shamatari (one of the three featured "cannibal" tribes) are grotesquely murdering some captured Yanomamo. Two men are dragging what looks like a stone axe wrapped with cloth up and down a girl's chest. Why are they doing that? They may be tenderising the meat in some way, but it's hard to be sure. The 'effect' as such is not particularly convincing, but neither are most of the others in the film. For some reason, it doesn't seem to matter. Most viewers don't seem to notice - not even the wig falling off the 'severed head' of Faye in the final massacre. So what power does Cannibal Holocaust possess? Does it have this power in spite of its bad effects, or partly because of them? The scene with the Shamatari is highly theatrical; it is a staged vision of hell. And the means that it uses are theatrical means.

Peter Hall, in an essay comparing the cinema to the stage, wrote that the miracle of theatre was that with a few bare boards and some simple props, one could create a world, a world that the audience would enter, and that would be completely real to them. Whereas in the cinema - one duff effect and the spell is broken, the magic is ruined! But perhaps this is a distinction between different kinds of film, as much as between theatre and cinema. Some directors are, after all, extremely theatrical. John Waters is a good example. The pantomime sets of Desperate Living are entirely convincing, albeit made out of scavenged trash and cardboard. Mortville is as real as if I saw it on the TV - maybe more so. The limitations of certain films - the technical limitations they have in terms of presenting the 'real' - signal to the audience that what they are watching is not merely real. What they are watching is not therefore a failure, but something with artistic intention like a play or a poem. Something, therefore, with artistic power. In a performance of Titus Andronicus, and I think too, in one of Sarah Kane's plays, blood was symbolised pouring from the wounds of the characters by using long red streamers. And yet the audience were still shocked and traumatised - perhaps all the more so. Imagine Cannibal Holocaust with FX by Tom Savini. It would be a film drained of its improvisatory, theatrical imagination, and hence most of its artistic authority. The best thing about the zombies in a Romero film is their simple grey make up with well-perfused fingers and eyelids. Night of the Living Dead in particular gains in power from the cheap effects. The worst thing is the realistic entrails, the slop and the showpiece dismemberments that do nothing to save or elevate Day of the Dead. They are too convincing - mere technical achievements. The audience look on with indifference.

Having said that, I don't mean to imply that a 'theatrical' effect is a bad one - only, that it will not be a seamless one, that it never aims at superrealist precision. The effects themselves will be all the more imaginative - but using the kind of simple stage tricks seen in Ringu, for example, when Sadako crawls from the TV set. Not difficult to work out how they did that! But it was a scene that drove a nail into the audience. It shouldn't be difficult to work out how they impaled the girl in Cannibal Holocaust, but even Italian judges and British customs officials were convinced it had 'actually happened'. It's not because these sort of people are stupid - as some would have us believe - and not because a more elaborate effect would have had some give-away CGI sheen, but because the bare-bones theatrical techniques signal the presence of an artistic as opposed to a technical vision, and have the most artistic power. And it is the heart of Cannibal Holocaust that people find so disturbing.

Peter Hall, in an essay comparing the cinema to the stage, wrote that the miracle of theatre was that with a few bare boards and some simple props, one could create a world, a world that the audience would enter, and that would be completely real to them. Whereas in the cinema - one duff effect and the spell is broken, the magic is ruined! But perhaps this is a distinction between different kinds of film, as much as between theatre and cinema. Some directors are, after all, extremely theatrical. John Waters is a good example. The pantomime sets of Desperate Living are entirely convincing, albeit made out of scavenged trash and cardboard. Mortville is as real as if I saw it on the TV - maybe more so. The limitations of certain films - the technical limitations they have in terms of presenting the 'real' - signal to the audience that what they are watching is not merely real. What they are watching is not therefore a failure, but something with artistic intention like a play or a poem. Something, therefore, with artistic power. In a performance of Titus Andronicus, and I think too, in one of Sarah Kane's plays, blood was symbolised pouring from the wounds of the characters by using long red streamers. And yet the audience were still shocked and traumatised - perhaps all the more so. Imagine Cannibal Holocaust with FX by Tom Savini. It would be a film drained of its improvisatory, theatrical imagination, and hence most of its artistic authority. The best thing about the zombies in a Romero film is their simple grey make up with well-perfused fingers and eyelids. Night of the Living Dead in particular gains in power from the cheap effects. The worst thing is the realistic entrails, the slop and the showpiece dismemberments that do nothing to save or elevate Day of the Dead. They are too convincing - mere technical achievements. The audience look on with indifference.

Having said that, I don't mean to imply that a 'theatrical' effect is a bad one - only, that it will not be a seamless one, that it never aims at superrealist precision. The effects themselves will be all the more imaginative - but using the kind of simple stage tricks seen in Ringu, for example, when Sadako crawls from the TV set. Not difficult to work out how they did that! But it was a scene that drove a nail into the audience. It shouldn't be difficult to work out how they impaled the girl in Cannibal Holocaust, but even Italian judges and British customs officials were convinced it had 'actually happened'. It's not because these sort of people are stupid - as some would have us believe - and not because a more elaborate effect would have had some give-away CGI sheen, but because the bare-bones theatrical techniques signal the presence of an artistic as opposed to a technical vision, and have the most artistic power. And it is the heart of Cannibal Holocaust that people find so disturbing.

... the metaphysical side of bad dreams

"This may seem strange, but I am happier than someone like Bunuel, who says he is looking for God. I have found him in the misery of others, and my torment is greater than Bunuel's. For I have realised that God is a God of suffering. I envy atheists; They don't have all these difficulties."

Lucio Fulci

Iron Rose

sweet, portentous lust - from Jean Rollin's "Rose de Fer"

Sometimes, when I necked with a stranger, I went

close to that - pheromone, sweat,

scorch, kiss of life - tasting in him

some male, unmothered world, and through him

a male world was tasting me.

Every time, I was pretending, without knowing,

that I could lay my body like a soul in his hands

and he would not take it. But he might. But he would not.

Sharon Olds

Friday, November 11, 2005

Thursday, November 10, 2005

"The unwanted unwanting the world"

THERE IS NO RIOT

Even that desperate gaiety is gone.

Empty bottles, no longer trophies

are weapons now. Even the cunning

grumble. "If is talk you want," she said,

"you wasting time with me. Try the church."

One time, it was because rain fell

there was no riot. Another time

it was because the terrorist forgot

to bring the bomb. Now, in these days

though no rain falls, and bombs are well remembered

there is no riot. But everywhere

empty and broken bottles gleam like ruin.

O MY COMPANION

This afternoon white sea-birds

were quiet, very quiet, until

a cloud over the sun fooled them

it was sunset. The fishes laughed

at the hook in the bait. The cork danced.

Where you are, I am. Lost and seeking

I question the waste. The wind

is blue smoke. From the fires

no flame sprouts. In the distance

day is a foreigner. If a child drowns

it is the sky's fault. If sea-birds stray

the sun's. O my companion.

FOR WALTER RODNEY

Assassins of conversation

they bury the voice

they assassinate, in the beloved

grave of the voice, never to be silent.

I sit in the presence of rain

in the sky's wild noise

of the feet of some who

not only, but also, kill

the origin of rain, the ankle

of the whore, as fastidious

as the great fight, the wife

of water. Risker, risk.

I intend to turn a sky

of tears, for you.

from Selected Poems by Martin Carter (1927 - 1997)

Even that desperate gaiety is gone.

Empty bottles, no longer trophies

are weapons now. Even the cunning

grumble. "If is talk you want," she said,

"you wasting time with me. Try the church."

One time, it was because rain fell

there was no riot. Another time

it was because the terrorist forgot

to bring the bomb. Now, in these days

though no rain falls, and bombs are well remembered

there is no riot. But everywhere

empty and broken bottles gleam like ruin.

O MY COMPANION

This afternoon white sea-birds

were quiet, very quiet, until

a cloud over the sun fooled them

it was sunset. The fishes laughed

at the hook in the bait. The cork danced.

Where you are, I am. Lost and seeking

I question the waste. The wind

is blue smoke. From the fires

no flame sprouts. In the distance

day is a foreigner. If a child drowns

it is the sky's fault. If sea-birds stray

the sun's. O my companion.

FOR WALTER RODNEY

Assassins of conversation

they bury the voice

they assassinate, in the beloved

grave of the voice, never to be silent.

I sit in the presence of rain

in the sky's wild noise

of the feet of some who

not only, but also, kill

the origin of rain, the ankle

of the whore, as fastidious

as the great fight, the wife

of water. Risker, risk.

I intend to turn a sky

of tears, for you.

from Selected Poems by Martin Carter (1927 - 1997)

Tuesday, November 08, 2005

Another Japanese tale of horror

PART ONE

PART ONEThere was once a girl of middling appearance and marriageable age who lived in a remote house with her parents. She used to sell candies in the nearest village. She would push round a wooden cart and the neighbourhood children would scramble up to it. The cart was a rather dilapidated one, but she made it attractive with bright coloured cloths. When the candies were sold, and her work finished for the day, she would walk the few miles back home. To anyone watching her as she made her way, it might seem that she was thinking. Not merely daydreaming, or turning things over in the everyday sense, but actively, furiously thinking. An onlooker might be reminded of ants, or of a cloud of mosquitos. There was something rather disturbing about it.

She had much the same manner at dinner, but her parents were used to it. As soon has she had finished, she marched out rather stiffly to her bedroom, and took out an old book with many hundreds of blank pages. This was her diary, and every night without fail she would fill out a page with whatever it was that she wrote - because no one to this day has any idea what she did write, or what it was that so troubled and preoccupied her. Her father had little interest in his daughter, and it would never have occured to him to read it, and her mother, with whom she made the candies each morning, had never learned to read or write.

An elderly man trudged his way up to the remote house one evening. From her room the girl could hear the old man and her father talking. Not unnaturally, in the course of her work in the village, she had attracted a number of admirers, and not just among the children. What was taking place that night, as her mother knelt by the table pouring saké, was a negotiation. And sure enough, when she arrived home the following evening and greeted her parents, her father informed her that she was going to be married, to a young farmer in the nearby village. He had noticed her as she lifted the cloth from the sweets on her cart, surrounded by a press of excited children, and he had watched her from a distance as she pushed her cart home, her head bent, and her long hair blown by the wind into tangles.

And that night, as every night, the girl wrote her diary, in lines now graceful and flowing, now jagged and broken.

She remembered him, vaguely. He had a yearning expression. He was the heir to a reasonable-sized farm and a substantial, if rather characterless, farmhouse. The wedding would take place in a matter of months, and now, whenever she wheeled her sweet-cart into the village, she avoided looking around at the houses and surrounded herself with the children.

It was around this time that her diary-activity became more intense and concentrated. Each night she would stay up until the early hours, straining her eyes at the pages.

Eventually the day came when she was to be married, and the night when she would be accompanied back to his farm by her husband, and the morning when she would have get up before sunrise, before even the birds, and set out her husband's clean clothes and prepare his breakfast. Each day would be like that, stretching out monotonously until what seemed like infinity, but her consolation, and her curse, was that each night she retired to their bedroom before him, writing and writing with intense concentration.

She refused to show her husband what she was writing, and indeed to say anything meaningful about what she was putting in her diary. She would glower at him horribly if he so much as approached it. For the first few months of his marriage, he was happy to humour her in this, and he did not treat it as an insult. He had been lonely a long time, and had long found her fascinating. He was glad to be married, and to have his food prepared for him. He felt grateful to heaven. And yet, as the months went by, the couple began to chafe against each another. He found her secretive devotion to the heavy book troubling, exasperating, and finally disgusting.

One afternoon as she walked into the village to buy provisions, he opened the cupboard in which she kept it, carefully, slowly removed it, and stared at its dark cover, challenging himself to open it. It was absurd, he felt, that he should even feel nervous about it. It was a hundred times-over his right as a husband to open the pages and discover for himself what she was writing. And at that moment the room became grey as a cloud crossed the sun, and a strange chill came over him.

to be continued...

A lonely ghost story from Japan

There was once a young man wandering by himself in the sun-dappled forest. He carried a bow in his hand and a quiver on his shoulder but he was not interested in hunting. He was absorbed in thinking. But not thinking anything in particular. It was one of those days when his thoughts seemed to weigh rather heavily on him, although if asked he could never say exactly what the trouble was.

Passing beneath a group of shady trees, he took a path that he did not remember noticing before, and emerged after a while into a large and beautiful clearing. In the middle of the clearing was what looked like a hunting lodge, built of wood, with shuttered windows and a wooden balcony at the front. There didn't seem to be anyone about. He called, but there was no reply. Deciding to take a closer look, he stepped up onto the balcony and approached the door, pressing his hand against it. At once it glided open and he saw the brightly shining face of a beautiful woman.

"How very strange to see you", she said. "I hardly see anybody. I live a very secluded life here in the forest". The young man was too shocked to speak. "But since you're here", she continued, "come in anyway, and I'll boil you up some tea".

The hallway led directly through to what looked like a kitchen. On either side were two plain wooden doors. She opened the door on the right and led the young man through into a sitting room. It was sparsely furnished with a low table and an old wooden chest. There were also a number of birds fluttering restlessly in little cages. She dropped some seeds into each before going to the kitchen, returning with a small pot of tea.

They talked for a long while and the conversation flowed naturally from the first, although it was hard to say exactly what it was they talked about. The young man simply had the feeling of time passing by delightfully. As the afternoon wore on, however, and he noticed the rays of the declining sun through the shutters, he said "I must have kept you for hours. Perhaps I ought to be making my way back".

"Oh no", she replied, "I was hoping you might stay to dinner. But there was something I was wondering if you could do for me".

"Anything", he said.

"I was hoping you could mind the lodge while I'm gone. I need to go away for a short while. I won't be long". She stood up and led him into the hallway. "Make yourself at home in the sitting room", she said, "or wander through into the kitchen. But there's one thing I want you to promise me".

"What's that?"

"That you won't.... You can go into any room in the lodge - but don't open this door". And she pointed to the door on the left.

"But why on earth not?" he asked, surprised.

"Because you mustn't", she replied. "I want you to promise me faithfully that you will not".

"Then I will not. Of course. Absolutely" the young man said.

She smiled and turned to leave. She had an eerily beautiful face. Stepping down onto the balcony, she walked towards the forest and was gone.

Of course the young man found this curious, and after returning to the sitting room and thinking about her beauty for a while, he began to feel strangely ill at ease. He walked back to the hallway and stood before the left hand door. It was a plain wooden door with nothing interesting about it. Nonetheless its very blankness seemed provoking. What could lie beyond it?

He had promised very faithfully not to go inside, and a promise was a promise, especially one made to such a beautiful woman. But suddenly the thought of her beauty crossed his mind like a shadow, and almost angered him. The feeling passed, and he returned to the sitting room to peer at the birds and set them aflutter by tapping their cages.

But after some minutes he returned to the hallway and stared outside. There was no sign of her returning. The left hand door caught his attention. Without thinking he placed his fingers on the handle. He snatched them away, but then slowly returned them. It was only a door after all, and he was naturally curious.

He thought of her beauty, and somewhere in his mind he felt a stab of hatred. She would never know, and he would certainly not admit it. That wouldn't stop them having a beautiful dinner that night, and him paying her elaborate compliments.

He looked outside. Again, there was no sign of her. After pausing for a while, he turned the handle.

He pushed open the door, and stepped inside.

The room was empty. He looked around - it was completely bare. Yet at the corner of his eye he caught a strange glimpse of feathers. At the edges of his hearing he had a vague sense of the fluttering of wings, and then everything seemed to vanish from around him.

He woke up to find himself lying face down and alone in a deserted field. It seemed to be the following morning. He wiped the dew from his clothes as he picked himself up. The woman, the lodge and the beautiful clearing had all disappeared, although the field he recognised. It was not far from his home. What had he done when he opened that door? And what had become of the woman? He went back in his mind over everything that had happened. He recalled it all quite clearly, and felt desolate.

And for many months afterwards he would search through the forest and try to find that shady path to the clearing. He never stopped thinking of the little wooden lodge and the beautiful woman.

He never found either again.

Passing beneath a group of shady trees, he took a path that he did not remember noticing before, and emerged after a while into a large and beautiful clearing. In the middle of the clearing was what looked like a hunting lodge, built of wood, with shuttered windows and a wooden balcony at the front. There didn't seem to be anyone about. He called, but there was no reply. Deciding to take a closer look, he stepped up onto the balcony and approached the door, pressing his hand against it. At once it glided open and he saw the brightly shining face of a beautiful woman.

"How very strange to see you", she said. "I hardly see anybody. I live a very secluded life here in the forest". The young man was too shocked to speak. "But since you're here", she continued, "come in anyway, and I'll boil you up some tea".

The hallway led directly through to what looked like a kitchen. On either side were two plain wooden doors. She opened the door on the right and led the young man through into a sitting room. It was sparsely furnished with a low table and an old wooden chest. There were also a number of birds fluttering restlessly in little cages. She dropped some seeds into each before going to the kitchen, returning with a small pot of tea.

They talked for a long while and the conversation flowed naturally from the first, although it was hard to say exactly what it was they talked about. The young man simply had the feeling of time passing by delightfully. As the afternoon wore on, however, and he noticed the rays of the declining sun through the shutters, he said "I must have kept you for hours. Perhaps I ought to be making my way back".

"Oh no", she replied, "I was hoping you might stay to dinner. But there was something I was wondering if you could do for me".

"Anything", he said.

"I was hoping you could mind the lodge while I'm gone. I need to go away for a short while. I won't be long". She stood up and led him into the hallway. "Make yourself at home in the sitting room", she said, "or wander through into the kitchen. But there's one thing I want you to promise me".

"What's that?"

"That you won't.... You can go into any room in the lodge - but don't open this door". And she pointed to the door on the left.

"But why on earth not?" he asked, surprised.

"Because you mustn't", she replied. "I want you to promise me faithfully that you will not".

"Then I will not. Of course. Absolutely" the young man said.

She smiled and turned to leave. She had an eerily beautiful face. Stepping down onto the balcony, she walked towards the forest and was gone.

Of course the young man found this curious, and after returning to the sitting room and thinking about her beauty for a while, he began to feel strangely ill at ease. He walked back to the hallway and stood before the left hand door. It was a plain wooden door with nothing interesting about it. Nonetheless its very blankness seemed provoking. What could lie beyond it?

He had promised very faithfully not to go inside, and a promise was a promise, especially one made to such a beautiful woman. But suddenly the thought of her beauty crossed his mind like a shadow, and almost angered him. The feeling passed, and he returned to the sitting room to peer at the birds and set them aflutter by tapping their cages.

But after some minutes he returned to the hallway and stared outside. There was no sign of her returning. The left hand door caught his attention. Without thinking he placed his fingers on the handle. He snatched them away, but then slowly returned them. It was only a door after all, and he was naturally curious.

He thought of her beauty, and somewhere in his mind he felt a stab of hatred. She would never know, and he would certainly not admit it. That wouldn't stop them having a beautiful dinner that night, and him paying her elaborate compliments.

He looked outside. Again, there was no sign of her. After pausing for a while, he turned the handle.

He pushed open the door, and stepped inside.

The room was empty. He looked around - it was completely bare. Yet at the corner of his eye he caught a strange glimpse of feathers. At the edges of his hearing he had a vague sense of the fluttering of wings, and then everything seemed to vanish from around him.

He woke up to find himself lying face down and alone in a deserted field. It seemed to be the following morning. He wiped the dew from his clothes as he picked himself up. The woman, the lodge and the beautiful clearing had all disappeared, although the field he recognised. It was not far from his home. What had he done when he opened that door? And what had become of the woman? He went back in his mind over everything that had happened. He recalled it all quite clearly, and felt desolate.

And for many months afterwards he would search through the forest and try to find that shady path to the clearing. He never stopped thinking of the little wooden lodge and the beautiful woman.

He never found either again.

At this point in time, millions of souls collect

to say McTeague's gilt tooth should not have been taken away

& other American tragedies

imaginary & real: Hart Crane in Paris, wreckt,

Adlai in London, looking on a day

for a terrible partner, a tease.

O yes, at this point in time the American soul

gathers its forces for the good of man

but it has memories.

Henry Adams denied this, & he was right

but for the few the place is crawling with ghosts

like lice in a pan.

When will the fire be turned on? and by whom?

heating the memory and soul alike

until both crisp.

Not soon, I wonder, but in some lead-shielded room

mistakes are being made like the Third Reich

perhaps, I lisp.

John Berryman, 4th July 1968

to say McTeague's gilt tooth should not have been taken away

& other American tragedies

imaginary & real: Hart Crane in Paris, wreckt,

Adlai in London, looking on a day

for a terrible partner, a tease.

O yes, at this point in time the American soul

gathers its forces for the good of man

but it has memories.

Henry Adams denied this, & he was right

but for the few the place is crawling with ghosts

like lice in a pan.

When will the fire be turned on? and by whom?

heating the memory and soul alike

until both crisp.

Not soon, I wonder, but in some lead-shielded room

mistakes are being made like the Third Reich

perhaps, I lisp.

John Berryman, 4th July 1968

Tuesday, November 01, 2005

Ròs buidhe

A flower for Nasrin Alavi, whose fascinating book We are Iran has just been published by Portobello Books. It is a compilation of articles on every imaginable subject by alert and courageous Iranian bloggers, interspersed with Alavi's analysis. It is a door into a world the Western reader might never imagine existed - over 64,000 blogs written in Persian!

"Reading We Are Iran, you have the sense that, for more reasons than are obvious, the worst thing that could possibly happen to Iran now would be US intervention."

Buy it here

Nasrin Alavi comments on Ahmadinejad and his recent speech in a letter to Christopher Dickey at his Shadowland Journal blog.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)